Sunday, February 24, 2008

Food for thought

Tuesday, February 19, 2008

The Supreme Court Has ( n o t ) Spoken...

Don't you feel safer already? I sure do... yeah.

Sunday, February 17, 2008

The Art of Losing's Not Hard to Master...

And speaking of the art of losing, she's the one who wrote the song that accompanied the best ending episode to any series I've seen, Six Feet Under:

Saturday, February 16, 2008

All Work and No Play?

I was so wiped out after driving back home from college that, after I got some groceries (a bit of lunch meat, yogurt, some chicken) I fell asleep before I even put it in the refrigerator. And I slept for over 12 hours. So much for the perishables. Since morning, I've read a D. H. Lawrence novella and half of a 75-page essay on scansion, done 3 loads of laundry (two more to go), and betrayed my resolution to eat healthy food by going to a nearby Mexican restaurant. While reading the rest of the essay (and possibly also while grading 20 term papers), I'll be listening to Silvestrov's Symphony No. 6, hopefully enough to have an idea of what to write for a review.

Yet to do this weekend--

grading of aforementioned papers

writing of two poetic masterpieces

writing of aforementioned review

This coming week I'll be reading the entire output of either Anne Sexton or Elizabeth Bishop for a paper due in two weeks, reading a decade's worth of the Georgia Review for another paper due in several weeks, and deciding what passage to write a 5-page essay on for my Modernist British Fiction class--for this last one, I'm wondering if I should go for the Lawrence, as my dislike of The Virgin and the Gipsy may make it an easier paper to write. I'd heard from some established author or other (who was it--Gary Snyder, Ellen Bryant Voigt?) that, though Lawrence wrote a great deal, he essentially wrote the same novel eight times over. I don't know if that's true, but The Virgin and the Gipsy is pretty damned sloppy writing. One of the characters, who is named, who comes in toward the end of the work is referred to as "the little Jewess" something on the order of five times per page. Not "she" or by her name: "the little Jewess." Occasionally, he will refer to her as "the tiny Jewess" for infrequent variety (who is this--Yentl-belle?), but that's about it. It would be fun to tear this book apart, but in all likelihood, I'll take the high road and go for something by Elizabeth Bowen or perhaps Dorothy Richardson.

The scansion essay calls.

Saturday, February 09, 2008

The immense stylizations o' Bananarama

For example, their collaborations with Fun Boy Three--

Their big hit had me interested in them at the time--

but they had little else to do but make dancier versions of 60s and 70s tunes, all again sung almost entirely in unison unless the chorus tricked them into doing otherwise...

Siobhan, the brunette, managed to redeem herself by marrying David Stewart of Eurythmics and forming Shakespear's Sister. They first came on the scene with a song called Heroine which has Siobhan running around in a wedding dress. The song , though it has its moments, is pretty much typical late 80s pop. Later, though, Shakespear's Sister had a song with one of the best videos of the early Nineties, directed by the wonderful Sophie Muller:

The video spoke heavily on certain levels to AIDS, the many deaths simply swept under the rug, Siobhan's appearance at the time was electrifying, there as Death-as-seductress, confident of winning. After this, they essentially dropped off the planet. Sophie Muller continued on, directing great videos for Eurythmics and Blur, among others.

Asleep in the Dark of You, It Feels Like I Never Saw Sun--Another Rabbit Hole

It also sounds a good deal smarter than her previous efforts. Her breakthrough hit of a few years back "Cant Get You out of My Head" was destined to be a big hit, but half the song being nothing but "Na-na-na" obviated the video of her wearing a gas station towel belt and two staples. I noticed the song title of her new single is the same as an 80s song by Stacy Q, the woman who brought hair crimping to the masses--millions of hapless teens baked their locks into brittle lasagna noodles for a full year before having to cut it all off. The Kylie song's melody is based heavily on the Stacy Q chorus motif of "I need you I need you."

I remember hearing the Stacy Q song on the bus radio on the way to high school in those dreary midwinter mornings just as we were having to pick up those hellish trailer court kids. The Stacy Q song is in turn a big rip-off of Madonna's own "Dress You Up"

--the "I need you I need you" is "all over all over" in the Madonna song, as evidenced by the videos supplied herein...

Blessed Be the Poor in Spirit

Hi all, just got this disc last week for review, and think it's kinda nifty For fans of ambient music--Eno, Feldman to some extent, and Aphex Twin's quieter moments--this might be worth looking into. A review will be showing up in the next week or so on Musicweb-International, the link to which is on the right side of the screen.

Lang makes the interesting argument that church masses shouldn't be there to fill the minds of parishioners with pictures, stories, etc, but--and I'm paraphrasing here-- are instead to empty the mind of earthly things, ostensibly so that it can be filled with things unearthly. The music for this mass works toward that end. The ambient-loving Davo likes this for the fact it is another ambient work I can listen to (it's just about the same length as Brian Eno's Neroli), the crotchety Davo is wondering why we have an hour-long extension of David Bowie's not-often heard ambient track Ian Fish, U.K. Heir off his overlooked TV soundtrack to the British TV show The Buddha of Suburbia. These two pieces are strikingly similar. No doubt you can hear snippets of the Bowie song on Itunes or elsewhere. If you like that, look this up.

Friday, February 08, 2008

and forms, and forms...

Sonnet sequences aren't dead. This from page 42

Ellen Bryant Voigt's amazing Kyrie, a sequence on the great flu epidemic--

How we survived: we locked the doors

and let nobody in. Each night we sang.

Ate only bread in a bowl of buttermilk.

Boiled the drinking water from the well,

clipped our hair to the scalp, slept in steam.

Rubbed our chests with camphor, backs

with mustard, legs and thighs with fatback

and buried the rind. Since we had no lambs

I cut the cat's throat, Xed the door

and put the carcass out to draw the flies.

I raised an upstairs window and watched them go--

swollen, shiny black, green-backed, green-eyed--

fleeing the house, taking the sickness with them.

And this from page 55:

Who said the worst was past, who knew

such a thing? Someone writing history,

someone looking down on us

from the clouds. Down here, snow and wind:

cold blew through the clapboards,

our spring was frozen in the frozen ground.

Like the beasts in their holes,

no one stirred--if not sick

exhausted or afraid. In the village,

the doctor's own wife died in the night

of the nineteenth, 1919.

But it was true: at the window,

every afternoon, toward the horizon,

a little more light before the darkness fell.

Tuesday, February 05, 2008

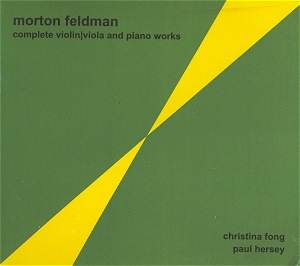

Feldman's Music for Viola and Piano--Recent recording

Morton Feldman’s star continues to rise in the years following his death in 1987. His music confuses some listeners, bores others, and challenges musicians with the prospect of performing mammoth works - in some instances running for five hours - that require utmost control and attention. This release from the minute label OgreOgress - so small they don’t give numbers to their releases - is a very important one for those who enjoy Feldman’s music. We now have several works that have not been recorded before.

One of these premier recordings is the opening [Sonata], composed in 1945 when Feldman was 19. It is a student piece and the most outwardly conventional of the works presented here, with three movements in fast/slow/fast sequence. Some would liken the sound of this piece to Bartók; for this reviewer, it calls up some of the Soviet composers of the 1920s and 1930s such as Roslavets or Lourié. The recording quality of this piece seems slightly muffled on headphones, but has very good presence on a living room system. The aesthetic of the recording suits the quiet later works especially well, with the microphone placement somewhat more distant than one would expect, allowing the ambience to act as a diffusing gauze over the ensemble.

The very short second work on the first disc, [Piece] of 1950, is sounds more like Feldman. The two instruments, interacting as if only by chance, play through their respective tones, the score bringing out many different colorations from the violin: harmonics, pizzicati, and bowed notes of widely varying pitch, as the piano plays chords of abruptly changing volume. Projection 4 and Extensions 1, the two following works, were written soon after [Piece], and are cut from the same cloth. The music here throws out spines; Feldman hasn’t yet taken to his later style of constant ppp dynamics, but over the course of these three pieces, one can see his development toward that end. The repetition or subtle colour changes of later Feldman are not here, but his sound-world is unmistakeable. The second piece from the Vertical Thoughts series, written just over a decade later than the Projection series and Extensions, has the breathless sense of suspension that marks much of Feldman’s later work.

Of the four pieces entitled The Viola in my Life, only the third is scored for viola and piano; the others are scored for the solo instrument with either chamber ensemble or orchestra. Here, the music, as well as the recording aesthetic, has receded even further from the footlights. The random sense of pitches and the occasionally confused sound has given way to a general motif of piano chords separated by rests.

Feldman, as some may already know, developed a fascination for oriental rugs, their patterns, their deviations, and this interest proved a springboard to his ideas of repetition, with slight variation, in the context of a larger — often much larger — work. Named after a mythical carpet, Spring of Chosroes is sparse, austere, contrasting with the image of a carpet of great intricacy and richness, yet corresponding in its subtly-varying repetition of motifs. Another find is the late piece [Composition] for solo violin of 1984 and the latest work presented in this release. It begins with alternating single notes and double-stops in a sort of breathing motif that the violinist carries throughout. This is a work of cold and quiet beauty which Christina Fong plays exceedingly well.

Of greatest interest to this reviewer are the two “For…” pieces that comprise the second disc of this collection. The first, For Aaron Copland, composed in 1981 and the much longer (by twelve times) For John Cage composed a year later, are haunting, bemusing, top-notch Feldman. John Cage bears a certain comparison to the Piano and String Quartet of 1985, but is far more varied regarding the repeated patterns and variation of motifs — Piano and String Quartet is a much more homogenous piece.

Saturday, February 02, 2008

Robert Hass's New Book

Robert Hass: Time and Materials: Poems 1997-2005

Ecco Press, 2007

87 pp.

$22.95

Hass has inspired a certain amount of controversy in his recent work, the vortex of it being the publication of “Bush’s War” in the American Poetry Review in March, 2006. The poem was chosen by Heather McHugh for inclusion in The Best American Poetry 2007, but not everyone is convinced that the poem constitutes Hass’s best. Time and Materials, though more heavily political than his last book, has some strong work that deserves not to be eclipsed by polemic.

From a casual glance at Time and Materials, which won the National Book Award in November, one gets the sense that this is a collection centered on a particular timeframe rather than a unifying literary concept. Hass, currently the chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, served as United States Poet Laureate from 1995 to 1997 and his weekly column in the Washington Post has recently appeared in book form, Now and Then: The Poet’s Choice Columns 1997-2000 (Shoemaker & Hoard, 2007). Some of the topics touched on in Time and Materials have been seen in earlier books of his, such as his mother’s alcoholism (“The World as Will and Representation”), which figured greatly in Sun Under Wood, as well as the difficulties of the writer to adequately present what is seen and felt (“The Problem of Describing Color” and “The Problem of Describing Trees”). Much here, actually, is an exploration on how to write and what to write about. This is done in painterly fashion in the most successful poems here, not only in terms of image and color, but also in their response to artwork. In “Art and Life” Vermeer’s Woman Pouring Milk is broken down into its individual components of cloth and pigment: “Ash and ash and chalky ash—is the stickiness of paint/ Adhering to the woven flax of the canvas, here/ Is the faithfulness of paint on paint on paint.” It is this layering that inhabits the best poems here, whether of paint or meaning or, as Hass writes in the title poem, time itself; “To make layers,/ As if they were a steadiness of days.”

It is interesting that 2001 serves as the arithmetical hyphen in the middle of the range of years found in the title. There is no indication that the poems in this collection are chronologically arranged, but as with the years that followed September 2001, the latter half of Time and Materials is preoccupied with the rise (or descent) of politics, the busting out of war, and war profiteering. This can be pretty shaky ground and has been the springboard for much well-intentioned—if inconsistently good—poetry. A casual glance at a title like “Bush’s War,” would certainly give a reader a measure of concern. Hass steers clear of bombast and banner-waving, moving instead away from the headlines to the internal, to a walk in Berlin at dusk; a realization that “it is a trick of the mind/ That the past seems just ahead of us, / As if we were being shunted there/ in the surge of a rattling funicular.” This sense of History repeating is arresting, but the political poetry here can verge on oversimplification—“Why do we do it? Certainly there’s a rage/ To injure what’s injured us. Wars/ Are always pitched to us that way.” Such acts indicate a “taste for power/ That amounts to contempt for the body.” The poem ends chillingly with Goethe: “Warte nur, bald ruhest du auch. Just wait./ You will be quiet soon enough.” The speaker in “A Poem” gets lost in comparisons of the Iraq war to Vietnam. In some instances, directness pulls through, as in “Ezra Pound’s Position” which expands the earlier poet’s indictment of world finance found in the Cantos, updating it with Halliburton and other foreign interests and the sad impacts of their involvement.

In the face of bleak prospects, in the face of war, Hass has wonderful moments of great beauty. Hass holds firm in the faith of the written word’s importance—the preoccupation with being able to get it right, either in describing the red of a flitting cardinal or the aspen “doing something” (what is it?) in the wind. It is this faith that becomes the greatest hope of those who “never accepted the cruelty in the frame/ Of things, brooded on your century, and God the Monster,/ And the smell of summer grasses in the world/ That can hardly be named or remembered/ Past the moment of our wading through them,/ And the world’s poor salvation in the word.” It is here and not in the political arguments, that we see Hass’s greatest success.

Friday, February 01, 2008

Nadine Sabra Meyer's Anatomy Theater

Nadine Sabra Meyer

The Anatomy Theater

Harper Perennial, 2006

ISBN 0-06-112217-3

$13.95

Some TV shows came to mind with regard to what this book has. For those who remember

The living would give anything,

it seems,

to know what the dead know,

to lift the pall

of flesh and find more than a charnel house…

This segment, from Dissection Prayers, at first seems a riff on Adrienne Rich’s “the truth the dead know,” but Meyer goes beyond that in this, her first collection. Each of the poems is written after a series of artworks. The book opens using the striking, grisly, and often whimsical anatomical prints of the 16th and 17th centuries, moving on to Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithographs and then on to a photograph of the speaker’s own surgically-removed endometriotic ovary. The lithographs and woodcuts the first section’s poems are based on are often disturbing in their whimsicality: partially-dissected cadavers going on walks or leaning against pedestals in pastoral landscapes, skeletons teaching lessons on anatomy, or cherubs taking body parts to the boiling tub for maceration. This wondrous and darkly humorous quality is well-executed by Meyer, speaking in timeless language that holds true for the most part. Occasionally it gets a bit too florid, as in Dissection Prayers’s final lines: “…their prayers/ are the susurrations of the cicada/ sloughing its shell.” or “The ice-grip stop-clenching your heart’s rondure” in the final poem of the collection, John Donne on His Deathbed. Aside from these minor instances, Meyer bypasses ornateness and goes for the greatly human. “In two hands, you carry yourself to doctors,” she writes in The Paper House, “offering up the body on a metal table, a steel shelf, a plate./ / You lay out the thing sick and invisible,/ and they look at you like you’re beautiful.” Like the early anatomists, these doctors are—as is Meyer, too, no doubt—fascinated with the machinery of the body, its toughness and fragility.

Meyer keeps the body pinned firmly to the center of each poem, first as something passive, something to be taken apart, decomposed, then as an active entity. The individual sections of the book cohere to the point that the whole collection could be seen as one long poem, as with Glück’s The Wild Iris. Across the collection, images recur, some of which are quite effective; the hoisting of a cadaver by rope and pulley, suspended from facial bones by hooks for the observers in the gallery, becomes the subject for a Toulouse-Lautrec lithograph, suspended by her teeth and spinning up to the trapeze. Others tend to be a bit more artificially placed, such as the case in Dancing at the Moulin Rouge, which begins in 1895, only to have a “plastic ring/ spun across the bar/ between forefinger and thumb.” Such an instance of anachronism jars the reader out of the poem, but this is a minor item in light of Meyer’s achievement here, which is great; unflinching, dark, and hopeful, where “in the steam of the newly-killed something like sound, like thought” might rise. Among other 16th century plates not used by Meyer is an old engraving, a portrait of Vesalius. The great anatomist is pictured looking toward the viewer, the fingers of his left hand curled around a flayed forearm; reading it, no doubt, like Braille. Meyer presents to us a tough and wonderfully unified collection; an illustration of the beauty that rises from the body’s text.